In the vast, cold expanses of Northeast China, where the ground freezes and thaws with the seasons, a silent transformation has been underway. Over the past five decades, the maximum freezing depth of the seasonally frozen ground (SFG) has been steadily decreasing, and a groundbreaking study led by Shuo Wang, published in the journal *Frontiers in Soil Science* (translated as “前沿土壤科学”), has brought this change into sharp focus.

Using a sophisticated machine learning model, Wang and his team have analyzed comprehensive data from ground meteorological monitoring stations and remote sensing reanalysis data to predict and understand the changes in maximum freezing depth (MFD). The results are striking: the MFD in Northeast China has been decreasing at an average rate of 8.54 cm per decade since 1975.

“This decrease in freezing depth is a clear indicator of climate change,” Wang explains. “It’s not just about the ground freezing less; it’s about how this change impacts our environment and our industries.”

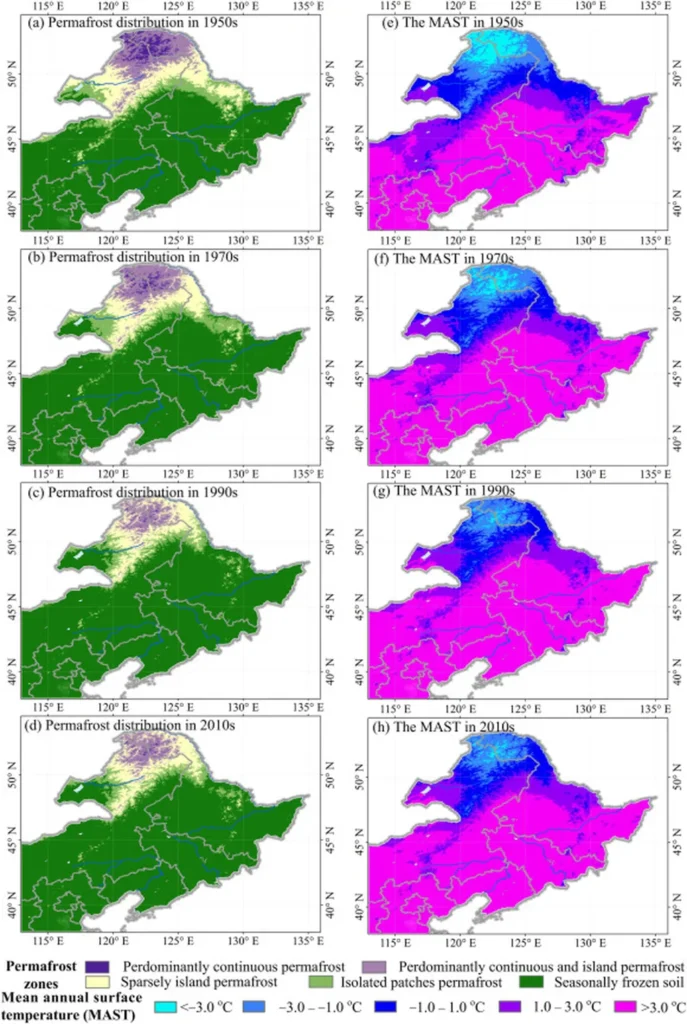

The study reveals that the average maximum freezing depths (AMFDs) have decreased from 136.71 cm in the 1970s to 104.58 cm in the past decade. This trend has significant implications for various sectors, particularly energy and construction.

For the energy sector, understanding these changes is crucial. “As the freezing depth decreases, the stability of structures built on frozen ground can be compromised,” says Wang. “This affects everything from oil and gas pipelines to wind turbines and other infrastructure. Accurate predictions of freezing depths are essential for planning and maintaining these structures.”

The study also highlights the increasing area of regions with freezing depths less than 160 cm, while areas with deeper freezing depths are on the decline. This shift can influence the design and construction of buildings, roads, and other infrastructure, as well as agricultural practices.

The machine learning model used in this study provides a powerful tool for predicting these changes. “Traditionally, we’ve lacked comprehensive data on freezing depths over long periods,” Wang notes. “This model allows us to fill in those gaps and make more accurate predictions, which is vital for developing climate adaptation strategies.”

As climate change continues to reshape our world, studies like this one are invaluable. They provide a scientific basis for environmental management and ecological protection, helping us to adapt and mitigate the impacts of a warming planet.

For the energy sector, the insights gained from this research could shape future developments, ensuring that infrastructure is built to withstand the changing conditions of the frozen ground. As Wang puts it, “Understanding these changes is not just about adapting to the past; it’s about preparing for the future.”

In the ever-evolving landscape of Northeast China, this research stands as a beacon, guiding us through the complexities of climate change and its far-reaching impacts.