In the quest to fortify coastal infrastructure against the corrosive might of seawater, researchers have turned to calcium sulfoaluminate (CSA) cements, a promising alternative to traditional Portland cement. A recent study led by Jihoon Park from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) has shed new light on how these cements behave when mixed with seawater and subjected to carbonation curing, a process that could have significant implications for the energy sector’s coastal and offshore projects.

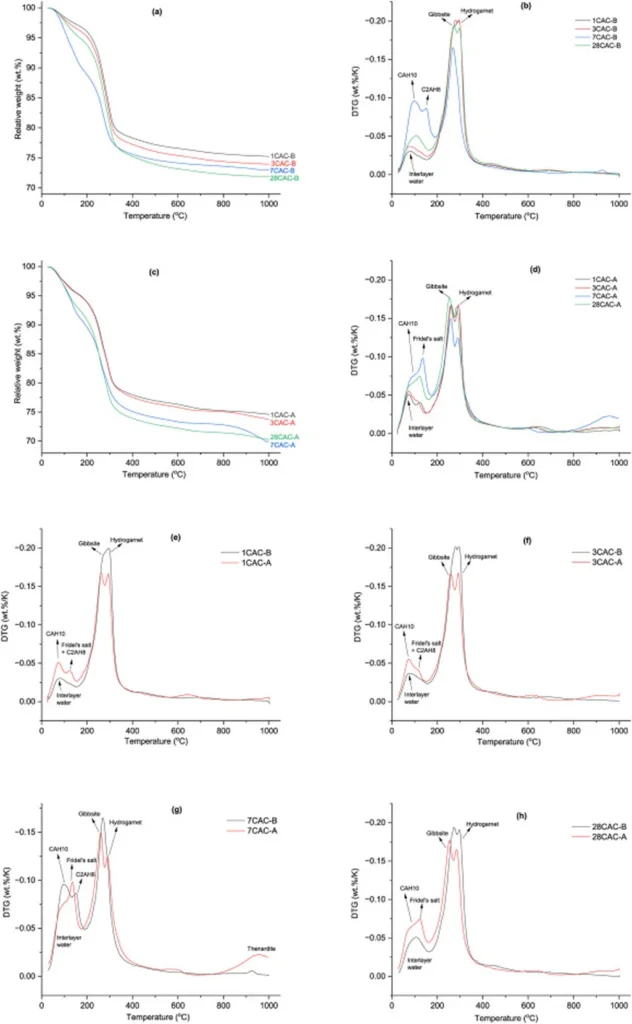

The study, published in the journal ‘Developments in the Built Environment’ (translated as ‘Advances in Construction and Building Technology’), investigated the phase evolution and mechanical properties of seawater-mixed CSA cements with varying m-values—a measure of the cement’s composition—under normal and carbonation curing conditions. The findings reveal a complex interplay between chloride binding capacity, compressive strength, and shrinkage behavior, all of which are critical factors in the durability and longevity of concrete structures.

Park and his team discovered that under normal curing conditions, samples with lower m-values exhibited higher chloride binding capacities, with the sample having an m-value of 0 showing a remarkable 160% increase compared to the sample with an m-value of 2.0. “This favorable formation of Kuzel’s salt in low m-value samples is a significant finding,” Park explained, “as it indicates a potential pathway for enhancing the chloride resistance of CSA cements in marine environments.”

However, the trade-off was a reduction in compressive strength. The sample with the lowest m-value had only 67% of the compressive strength of the sample with the highest m-value, along with increased total shrinkage. This presents a challenge for engineers and architects aiming to balance durability and strength in their designs.

The study also explored the effects of carbonation curing, a process that introduces carbon dioxide to accelerate the curing of concrete. While carbonation curing led to the decomposition of AFm phases, resulting in a loss of chloride binding capacity across all samples, it also mitigated total shrinkage up to 14 days. However, carbonation-induced shrinkage eventually prevailed, leading to increased total shrinkage and surface cracking in all samples, with severity depending on the m-value.

The implications of this research for the energy sector are profound. Coastal and offshore infrastructure, such as wind farms, oil rigs, and desalination plants, are constantly battling the corrosive effects of seawater. The findings suggest that by carefully tuning the m-value of CSA cements and optimizing curing processes, engineers could develop more durable and resilient concrete structures that can withstand the harsh marine environment.

Moreover, the enhanced chloride binding capacity observed in low m-value samples could potentially reduce the need for additional protective measures, such as coatings or barriers, thereby lowering construction costs and simplifying maintenance. “This research opens up new avenues for the application of CSA cements in the energy sector,” Park noted, “particularly in areas where traditional Portland cement has struggled to meet the demands of the marine environment.”

As the world continues to grapple with the challenges of climate change and the need for sustainable energy solutions, the insights gained from this study could play a pivotal role in shaping the future of coastal and offshore infrastructure. By pushing the boundaries of cement technology, researchers like Park are not only advancing the field of construction but also contributing to the broader goals of energy security and environmental sustainability.