In the bustling, densely populated streets of Dhaka, Bangladesh, a silent threat looms—air pollution. It’s a challenge that many rapidly developing countries face, and one that demands urgent attention. Enter Anuva Bhowmick, a researcher from the Centre for Smart Infrastructure and Digital Construction at Swinburne University of Technology, who has been working on a solution that could revolutionize air quality monitoring in resource-limited settings.

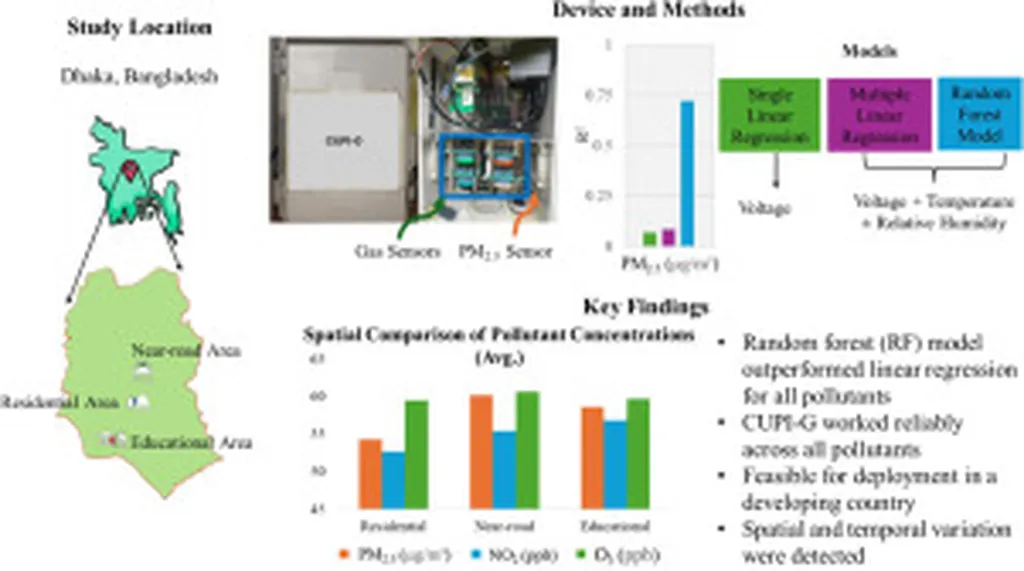

Bhowmick and her team have been validating the performance of the CUPI-G, a low-cost air quality monitoring device, in the heart of Dhaka. The device, equipped with electrochemical sensors, measures a range of pollutants including PM2.5, CO, NO, NO2, and O3. The results, published in the journal ‘Atmospheric Environment: X’ (translated to English as ‘Atmospheric Environment: New Research’), are promising.

The CUPI-G was deployed across multiple sites, from residential areas to bustling roadways and educational institutions. The data collected was validated using both statistical and machine learning approaches. The random forest model, in particular, showed impressive results. “The random forest model, especially when incorporating relative humidity, demonstrated superior performance in predicting pollutant concentrations,” Bhowmick explains. “For instance, we achieved a high correlation coefficient for O3 with an R2 value of 0.798 and low error metrics like RMSE of 3.594 ppb and MAPE of 4.812%.”

However, the team found that the model’s accuracy decreased when applied outside the training humidity range, highlighting the need for broader validation datasets. Despite this, the CUPI-G device was validated without using relative humidity as a factor and was found to still perform adequately.

The two-month spatial analysis revealed some stark findings. The hourly average of PM2.5 and O3 concentrations peaked near roadways, with PM2.5 reaching 89 μg/m3 and O3 at 66.50 ppb. NO2 levels were highest in the residential area at 63.49 ppb. These findings underscore the urgent need for detailed spatial and temporal data to inform public health advisories and policy interventions.

The implications for the energy sector are significant. Accurate, real-time air quality data can inform energy production and consumption patterns, helping to reduce emissions and improve public health. Low-cost monitoring devices like the CUPI-G could be a game-changer, enabling the expansion of air quality monitoring networks in resource-limited settings.

As Bhowmick puts it, “The CUPI-G device provides a reliable and cost-effective solution for expanding air quality monitoring networks. This is crucial for public health advisories and policy interventions, particularly in rapidly developing countries like Bangladesh.”

This research could shape the future of air quality monitoring, paving the way for more sophisticated, cost-effective solutions that can be deployed on a large scale. It’s a step towards a future where clean air is not a privilege, but a right.