In the quest for advanced gas detection technologies, a team of researchers led by Annelot Nijkoops from the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano in Italy has made significant strides in understanding and improving conducting polymer (CP)-based ammonia (NH3) sensors. Published in the Journal of Physics Materials, their work offers a comprehensive review of the current state and future potential of these sensors, which are poised to revolutionize various industries, including energy and healthcare.

Conducting polymers are highly sensitive to ammonia at room temperature, making them ideal for applications ranging from environmental monitoring to biomedical diagnostics. “The ability to detect ammonia levels in breath, from parts per million to parts per billion, can aid in diagnosing health conditions like liver and kidney dysfunction,” explains Nijkoops. This sensitivity is particularly valuable in the energy sector, where ammonia is a critical component in various processes, including fuel cells and refrigeration systems.

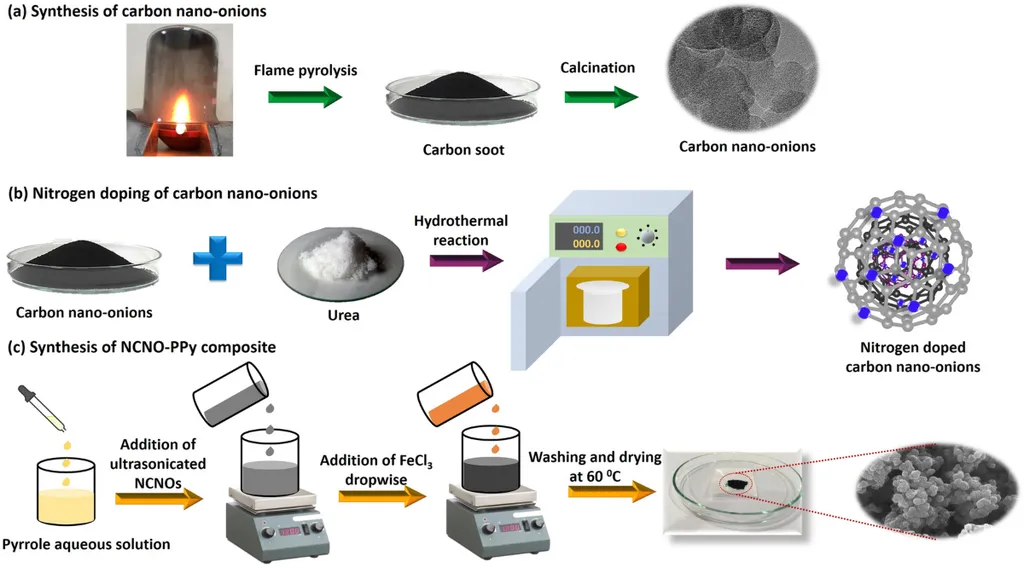

The review focuses on several types of conducting polymers, including P3HT, PEDOT, PPy, and PANI, evaluating their performance in terms of response time, selectivity, stability, repeatability, and sensitivity to environmental factors like humidity and temperature. One of the key findings is the role of porous structures and gas diffusion mechanisms in enhancing sensor performance. “Porous structures can significantly improve the sensitivity and response time of these sensors,” Nijkoops notes. This is crucial for applications where rapid and accurate detection is essential, such as in industrial settings where ammonia leaks can pose significant risks.

The mechanical flexibility of these sensors is another highlight, making them suitable for integration into flexible and wearable devices. This flexibility opens up new possibilities for real-time monitoring in various environments, from industrial plants to medical facilities. However, the research also identifies several challenges that need to be addressed. Poor selectivity due to interference from similar gases, sensitivity loss caused by humidity-induced polymer swelling, and instability from temperature fluctuations are among the key issues.

Nijkoops emphasizes the need for standardized testing protocols to facilitate performance comparisons. “The lack of standardized protocols complicates the evaluation and comparison of different sensors,” she says. This standardization would not only improve the reliability of the sensors but also accelerate their commercialization and adoption in various industries.

Looking ahead, the research suggests several avenues for future exploration. Improving the porosity of conducting polymers, understanding the interactions between gases and polymers, developing stable composites, and exploring new conducting polymers for enhanced ammonia sensing are all areas ripe for further investigation. These advancements could lead to more robust, reliable, and versatile sensors that meet the demands of diverse applications.

As the energy sector continues to evolve, the need for advanced gas detection technologies becomes increasingly critical. The insights provided by Nijkoops and her team offer a roadmap for developing next-generation sensors that can operate efficiently and effectively in challenging environments. Their work not only advances our understanding of conducting polymer-based sensors but also paves the way for innovative solutions that can drive progress in the energy sector and beyond. Published in the Journal of Physics: Materials, this research is a testament to the power of interdisciplinary collaboration and the potential of cutting-edge materials science to address real-world challenges.