In the heart of the Amazon, a silent battle is unfolding beneath our feet, one that could reshape our understanding of carbon sequestration and sustainable aquaculture. Francisco Ruiz, a soil scientist from the Department of Soil Science at the “Luiz de Queiroz” College of Agriculture, University of São Paulo (ESALQ/USP), has been delving into the intricate world of soil organic matter (SOM) in mangrove forests converted to shrimp farms. His findings, recently published in *Frontiers in Soil Science* (which translates to *Frontiers in Soil Science*), are a wake-up call for the energy and aquaculture sectors alike.

Mangroves, nature’s carbon sinks, are increasingly threatened by the expansion of shrimp farming. But what happens to the soil when these ecosystems are converted? Ruiz’s study sheds light on the long-term impacts of shrimp farming on SOM quality and carbon sequestration. “Pristine mangrove soils are rich in organic carbon, with a high carbon-to-nitrogen ratio and stable isotopic signatures,” Ruiz explains. “They’re a treasure trove of lignin, carbohydrates, and polyaromatic compounds, making them highly resilient and efficient at storing carbon.”

However, the story changes dramatically when mangroves are converted to shrimp ponds. Ruiz’s team found that these soils had significantly lower organic carbon content, lower carbon-to-nitrogen ratios, and enriched isotopic signatures, indicating nitrogen enrichment from shrimp feed. “The SOM in these converted areas is lipid-rich and thermally less stable,” Ruiz notes. “This means that not only are we losing carbon storage capacity, but the remaining SOM is more susceptible to degradation.”

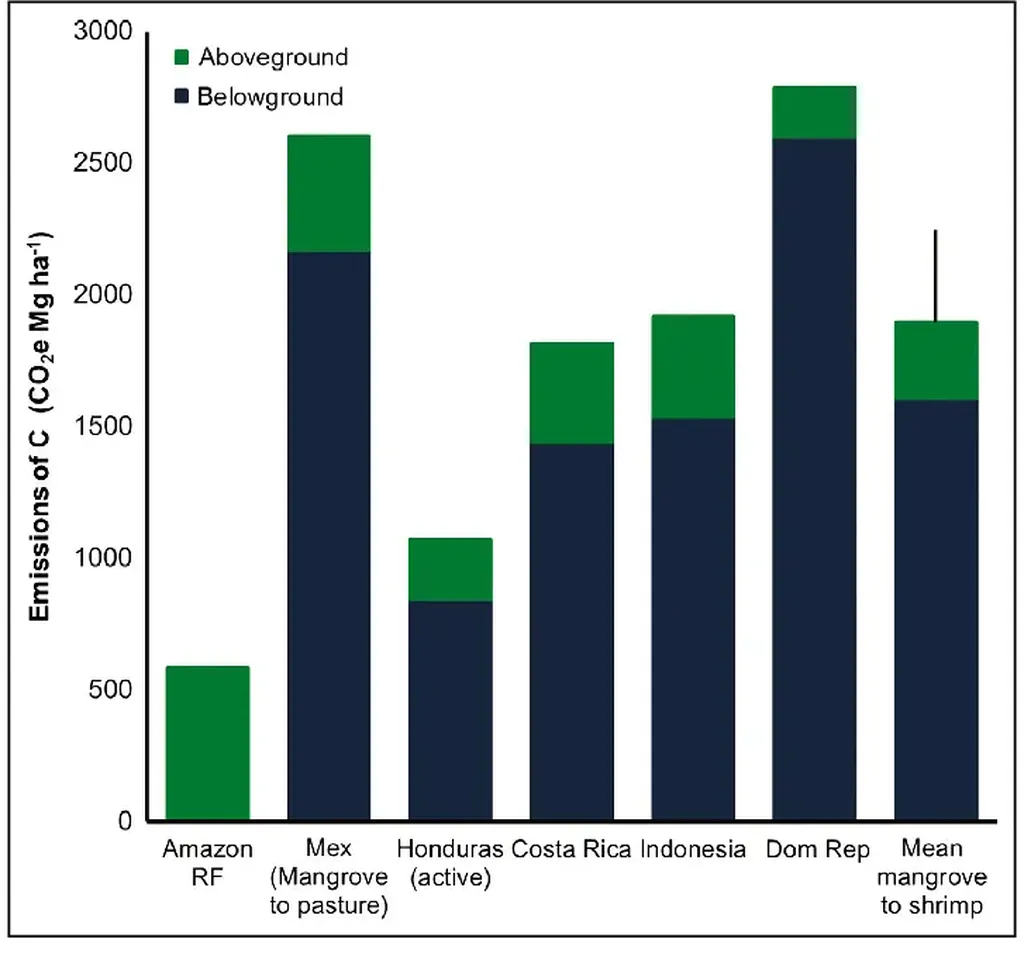

The implications for the energy sector are profound. Mangroves play a crucial role in carbon sequestration, helping to mitigate climate change. The degradation of SOM in these ecosystems could undermine their carbon storage potential, potentially impacting carbon credit markets and renewable energy projects that rely on these ecosystems for offsetting emissions.

But there’s a glimmer of hope. Mangroves adjacent to shrimp ponds showed only minor alterations in SOM, suggesting a high degree of resilience. However, Ruiz warns that effluent-driven SOM mineralization and reduced thermal stability pose latent risks. “It’s a delicate balance,” he says. “While adjacent mangroves may seem resilient, they’re not immune to the impacts of shrimp farming.”

So, what’s the way forward? Ruiz advocates for stricter regulations on effluent discharge and more sustainable aquaculture practices. “We need to find a balance between aquaculture expansion and environmental conservation,” he stresses. “This is not just about protecting mangroves; it’s about safeguarding our planet’s carbon sequestration capacity.”

As the world grapples with climate change, Ruiz’s research serves as a stark reminder of the delicate balance between economic development and environmental conservation. It’s a call to action for the energy and aquaculture sectors to work together, to innovate and adapt, to ensure that our pursuit of progress doesn’t come at the cost of our planet’s future. After all, the battle for the Amazon’s soil is not just a Brazilian issue; it’s a global one, and it’s one we can’t afford to lose.