In the realm of structural engineering and construction, a groundbreaking study has emerged that could reshape how we design and build complex surfaces. Sergey N. Krivoshapko, a researcher from RUDN University, has delved into the intricate world of developable surfaces with two director curves, publishing his findings in the journal “Structural Mechanics of Engineering Constructions and Buildings” (translated from Russian as “Stroitelnaya Mekhanika Inzhenernykh Konstruktsiya i Sooruzhenii”). His work promises to bridge the gap between theoretical mathematics and practical applications, offering new possibilities for industries ranging from architecture to energy.

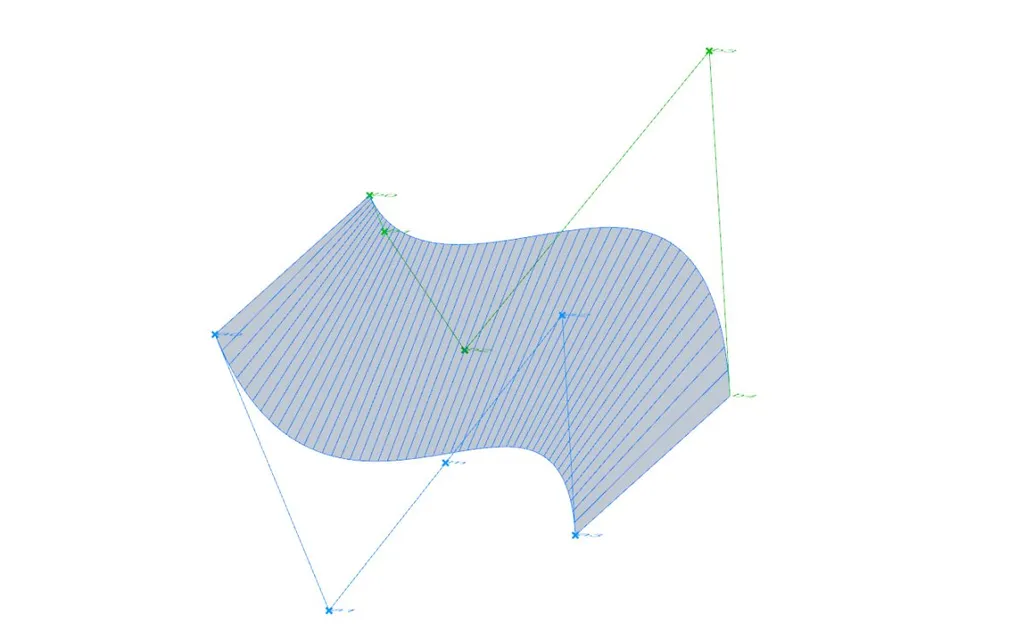

Developable surfaces are essentially surfaces that can be flattened into a plane without distortion, making them crucial for manufacturing and construction processes. Krivoshapko’s research focuses on four types of these surfaces, each defined by two supporting algebraic curves of the second order. These curves can lie in either parallel or intersecting planes, a nuance that significantly impacts the surface’s properties and potential applications.

“Understanding the behavior of these surfaces is like unlocking a new tool in our design toolkit,” Krivoshapko explains. “By mastering the construction techniques and parametric equations of these surfaces, we can create structures that are not only aesthetically pleasing but also structurally efficient.”

The study provides a detailed analysis of three types of developable surfaces, complete with visualizations to aid comprehension. For the fourth type, where the supporting curves have intersecting axes in intersecting planes, Krivoshapko offers a comprehensive construction technique and method for obtaining parametric equations. This is illustrated through three practical examples, making the theoretical concepts more accessible and applicable.

One of the most compelling aspects of this research is its potential impact on the energy sector. The ability to design and construct thin shells with curvilinear conjugate non-orthogonal coordinates could revolutionize the way we build energy infrastructure. From more efficient solar panel arrays to advanced wind turbine blades, the applications are vast and varied.

“Imagine a future where our energy infrastructure is not only more efficient but also seamlessly integrated into the natural landscape,” Krivoshapko envisions. “This research brings us one step closer to that reality.”

The study also highlights the lack of research on the strength of thin shells in the form of these developable surfaces. This gap presents a significant opportunity for future research, which could further enhance the practical applications of these surfaces in various industries.

As we look to the future, Krivoshapko’s work stands as a testament to the power of interdisciplinary research. By combining advanced mathematics with practical engineering, he has opened new avenues for innovation and development. For professionals in the construction and energy sectors, this research is not just a theoretical exploration but a call to action—to explore, adapt, and implement these findings in real-world applications.

In the rapidly evolving field of structural engineering, Krivoshapko’s contributions are a beacon of progress, illuminating the path forward for a more efficient and innovative future. As the world continues to demand more from its infrastructure, researchers like Krivoshapko are stepping up to meet the challenge, one developable surface at a time.